Wednesday, August 30, 2006

While the Doc's Away

On a technical note

Hmmmm. . . .

Whether we like it or not, the American public has time and again shown itself to be as interested in polygamists and 10-year-old murder cases as in the drowning of an American city. And it's no use only blaming the media for this: TV producers go where the ratings are, and the trashier the story, the bigger the audience has shown itself to be. Journalists are only one part - though an important one, since they set the tone for the coverage -- of this larger social reality, but it's still a shame that on a day when the nation mourns the deaths of hundreds of its citizens, some newscasts can't seem [to] break away from the trash long enough to give the story its due.The whole article (from our friends at Columbia Journalism Review) is worth your time.

From across the pond

In future, as newspapers fade and change, will politicians therefore burgle their opponents' offices with impunity, and corporate villains whoop as they trample over their victims? Journalism schools and think-tanks, especially in America, are worried about the effect of a crumbling Fourth Estate. Are today's news organisations “up to the task of sustaining the informed citizenry on which democracy depends?” asked a recent report about newspapers from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, a charitable research foundation.

Nobody should relish the demise of once-great titles. But the decline of newspapers will not be as harmful to society as some fear. Democracy, remember, has already survived the huge television-led decline in circulation since the 1950s. It has survived as readers have shunned papers and papers have shunned what was in stuffier times thought of as serious news. And it will surely survive the decline to come. That is partly because a few titles that invest in the kind of investigative stories which often benefit society the most are in a good position to survive, as long as their owners do a competent job of adjusting to changing circumstances.Publications like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal should be able to put up the price of their journalism to compensate for advertising revenues lost to the internet—especially as they cater to a more global readership. As with many industries, it is those in the middle—neither highbrow, nor entertainingly populist—that are likeliest to fall by the wayside. The usefulness of the press goes much wider than investigating abuses or even spreading general news; it lies in holding governments to account—trying them in the court of public opinion. The internet has expanded this court. Anyone looking for information has never beenbetter equipped. People no longer have to trust a handful of national papers or, worse, their local city paper. News-aggregation sites such as Google News draw together sources from around the world. The website of Britain's Guardian now has nearly half as many readers in America as it does at home.

In addition, a new force of “citizen” journalists and bloggers is itching to hold politicians to account. The web has opened the closed world of professional editors and reporters to anyone with a keyboard and an internet connection. Several companies have been chastened by amateur postings—of flames erupting from Dell's laptops or of cable-TV repairmen asleep on the sofa. Each blogger is capable of bias and slander, but, taken as a group, bloggers offer the searcher after truth boundless material to chew over. Of course, the internet panders to closed minds; but so has much of the press.

That's now you they're talking about, by the way. Do we need to fear for the republic, or is it in capable hands?

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

A gentle, but firm, lecture from the Doc

Let's set aside the substance for the moment. Your post, let me gently suggest, violates the spirit of discourse I have suggested we abide by. Edit your comment, and treat the poster with more respect, as you would like to be treated, I presume. Feel free to disagree. But don't resort to rhetoric and ad hominem attacks -- why suggest the poster has been "______" for example? Surely [his/her] arguments are neither irrational nor unfounded -- treat them seriously, point out your areas of disagreement, and create a space for civilized, respectful, dialog. The more important the politics (and, arguably, few things are more important than _____), the more likely smart, thoughful people are to disagree. That's the nature of deliberative democracy. Don't assume that people who see the political world differently than you do are stupid, rabid ideologues, ill-informed, or have bad intentions. Most don't. Lecture finished! Take another stab at it. . . .Let's not take what passes for political "debate" on TV, in the print media, and on many political blogs as our model. Let's do it better, and hold ourselves to much higher standards.

UPDATE: And, hey, don't be discouraged if you, too, get a message like this from C-Doc. This is a learning process, one with a not-insignificant learning curve. Part of what I'm hoping we'll learn over the course of the semester is a new standard for political debate and persuasive argumentation. The kind of writing I'm asking you to do will be new for most of you. I get that (C-Doc didn't just fall off the, ahem, turnip truck, you know). If by mid-semester I'm making the same observations and comments, well, then we have problems. But for now, not to worry -- it's all part of the process. So, relax, have fun. . . but play nice!

Friday, August 25, 2006

Stop it. Stop this. Stop.

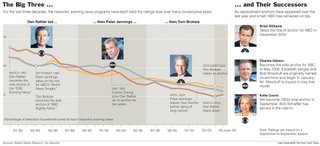

For those so inclined, here's a lazy-person's way of suggesting to the "Big Three" networks that maybe, just maybe, there might be more of import to report -- or to lead the newsbroadcast with (heavy sigh) -- than prurient coverage of a guy who probably had nothing to do with a ten-year-old murder. Is signing a petition the most effective way of making your voice heard? Nope. But that's not to suggest that such things do not matter, or that they cannot have influence.

For those so inclined, here's a lazy-person's way of suggesting to the "Big Three" networks that maybe, just maybe, there might be more of import to report -- or to lead the newsbroadcast with (heavy sigh) -- than prurient coverage of a guy who probably had nothing to do with a ten-year-old murder. Is signing a petition the most effective way of making your voice heard? Nope. But that's not to suggest that such things do not matter, or that they cannot have influence.On the topic of things that might matter more, again for those so inlined, there's a rally Sunday, September 17, 2:00 PM, in New York's Central Park, to (yet again) try to draw attention to the continuing genocide in Darfur. Numbers matter, and such things can, in truth, have influence, not least because the more people there are there, the more media coverage the event is likely to receive, and the more likely government(s) might feel pressured (out of electoral self-interest, if nothing else) to act.

And a fall afternoon in the park is a rather painless way of communicating to your government, and communing with your fellow citizens. Pack a lunch. Make a day of it.

Everything new is old again, Part II

Someone told me the next-generation iPod is going to have live-broadcast capability,” he said. “I always keep saying, ‘Are we gonna just call it a radio at that point?’”

Thursday, August 24, 2006

How FAIR?

During his August 21 press conference, George W. Bush responded to a question about the Iraq War by saying that "sometimes I'm happy" about the conflict. But many readers and TV viewers never heard the remark, since journalists edited the statement to save Bush any possible embarrassment.

Bush's unedited comment was as follows:Q: But are you frustrated, sir?

BUSH: Frustrated? Sometimes I'm frustrated. Rarely surprised. Sometimes I'm happy. This is -- but war is not a time of joy. These aren't joyous times. These are challenging times, and they're difficult times, and they're straining the psyche of our country. I understand that.

Viewers of CBS Evening News (8/21/06) saw a carefully edited version of that response—one better suited to presenting Bush as serious and concerned with the effects of the war. Reporter Bill Plante previewed the answer by saying that Bush "conceded that daily reports of death and destruction take a toll, both on the nation and on him." The edited quote that followed:Frustrated? Sometimes I'm frustrated, rarely surprised. These aren't joyous times. These are challenging times, and they're difficult times. And they're straining the psyche of our country. I understand that.

CBS was not alone in massaging Bush's response—many outlets excised Bush's "happy" remark, or found other ways to clean up Bush's performance.

So what's my complaint??

Guesses?

Re-read the first paragraph. What's wrong? They say his remarks were edited. That's true, and they quote the broadcasts. Fine, so far. But then they impute motives, telling us why Bush's remarks were edited. Problem? No evidence given. We don't know why the President's words were edited. We could guess, but that's all it would be. And that's all that FAIR is doing here.

It's a shame, because it undermines their larger, and more important, point: no news source should edit someone's comments in a manner that alters their meaning. Ever. There, I've gone and done it, an ironclad rule. We'll call it CrankyDoc's First Principle of Not-Crappy Journalism and Intellectually Honest Debate.

Facts! demanded the awful Gradgrind

in Charles Dickens's Hard Times. Today, I'll be your Gradgrind.

I draw your attention to this fine first post at Chef Shalom's Rockin' Blog (you have to love the title). No really. You have to. I insist.

This post is in many ways just the sort of thing I'm looking for to start -- for you all to begin to think about which stories are reported (and which are not), and how they are reported.

But as a social scientist, I am always most convinced by the careful marshalling of evidence that leads me to a conclusion, and less persuaded by mere assertion, or the repetition of "conventional wisdom" (what everybody supposedly knows to be true).

As we move forward, think about whether you are providing the reader with enough information, and the clear, causal logic to sustain your claim. So, to take one example, Chef writes:

the NYTimes has focused its headlines mainly on the images in Lebanon

Maybe true, maybe not. I don't know, because the good Chef offers the reader no evidence to support the claim, nor does he share with us the thinking that leads him to this conclusion. Maybe he's right, maybe he's partly right, maybe he's wrong.

So, as a social scientist, I would say to the Chef, and to all of you: unlike many questions we concern ourselves with (can war be just? what should the tax rate be? who should be the next President?) there is a "right" answer to this question. We can know this. How?

Here's one way:

- choose a logical period of time that does not skew (bias) your selection;

- examine all photos/headlines of the events in question (see Nexis, in the library's database collection -- it's easy to use, and fun for the whole family!);

- count and categorize them as fairly as you can (in a way that as few as possible fair-minded people would disagree with). Even better, have someone else count and categorize them, too: do you arrive at essentially the same conclusion?;

- examine your evidence.

What are the results? What's the answer? Did Chef get it right?

To paraphrase Cuba Gooding in Jerry Mcguire, "Show me the data! Show. . .me. . . the. . . data!"

All that said, to Chef (apologies for picking on him a bit -- but everyone will get their turn!): excellent start. Keep going!

Monday, August 21, 2006

Not surprised, just disappointed

TV Networks Focus on JonBenet Ramsey Case Over NSA Ruling

The major court ruling on the National Security Agency surveillance program has received scant coverage from the nation’s three major networks. On Thursday, ABC, CBS and NBC all led their nightly broadcasts with the latest in the 1996 murder case of child beauty queen JonBenet Ramsey. ABC devoted twice as much time in its broadcast to Ramsey as it did to the NSA story. CBS offered seven times as much airtime to Ramsey as it did to the NSA story. And NBC devoted 15 times more airtime to Ramsey.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

Saturday, August 19, 2006

Priorities, priorities

Number of reporters contributing to Friday's front page New York Times story on the JonBenet Ramsey case: 13

Number of reporters contributing to Friday's front page New York Times story on the federal court ruling that the NSA warrantless wiretapping program is unconstitutional: 2

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Social Science Defined

This recent definition, from "A Normative Turn in Political Science" by Boston University's John Gerring and Joshua Yesnowitz (Polity 38, no. 1, January 2006) seems a fine starting point:

. . .although the academy can lay claim to social utility, only social science must pursue that goal in a fairly direct and unmediated fashion. Art for art's sake has some plausibility, and science for science's sake might also be argued in a serious vein. But no serious person would adopt as her thesis social science for social science's sake. Social science is science for society's sake. These disputes look to provide answers to questions of pressing concern, or questions that we think should be of pressing concern, to the general public. We look to pursue issues that bear upon our obligations as citizens in a community -- issues related, perhaps, to democracy, equality, justice, life-satisfaction, peace, prosperity, violence, or virtue, but in any case, issues that call forth a sense of duty, responsibility, and action.

And, indeed, I approach the study of Media and Politics with a bias -- not a left/right, liberal/conservative, Democrat/Republican bias (although I do have my own policy preferences, to be sure), but with a normative bias about the role of mass media in a healthy democracy. I align myself on this with Alexis deTocqueville, one of the most thoughtful early observers of the nascent American republic:

The argument has been made more recently, and more entertainingly, by Jon Stewart, in his infamous appearance on the now-defunct Crossfire.WHEN men are no longer united among themselves by firm and lasting ties, it is impossible to obtain the co-operation of any great number of them unless you can persuade every man whose help you require that his private interest obliges him voluntarily to unite his exertions to the exertions of all the others. This can be habitually and conveniently effected only by means of a newspaper; nothing but a newspaper can drop the same thought into a thousand minds at the same moment. A newspaper is an adviser that does not require to be sought, but that comes of its own accord and talks to you briefly every day of the common weal, without distracting you from your private affairs.

Newspapers therefore become more necessary in proportion as men become more equal and individualism more to be feared. To suppose that they only serve to protect freedom would be to diminish their importance: they maintain civilization. I shall not deny that in democratic countries newspapers frequently lead the citizens to launch together into very ill-digested schemes; but if there were no newspapers there would be no common activity. The evil which they produce is therefore much less than that which they cure.

The effect of a newspaper is not only to suggest the same purpose to a great number of persons, but to furnish means for executing in common the designs which they may have singly conceived. The principal citizens who inhabit an aristocratic country discern each other from afar; and if they wish to unite their forces, they move towards each other, drawing a multitude of men after them. In democratic countries, on the contrary, it frequently happens that a great number of men who wish or who want to combine cannot accomplish it because as they are very insignificant and lost amid the crowd, they cannot see and do not know where to find one another. A newspaper then takes up the notion or the feeling that had occurred simultaneously, but singly, to each of them. All are then immediately guided towards this beacon; and these wandering minds, which had long sought each other in darkness, at length meet and unite. The newspaper brought them together, and the newspaper is still necessary to keep them united.

Watch the clip, think about Tocqueville, and ask yourself: how deep is the harm that lazy, simple-minded, contentious and insipid journalism (or, as the bloggers say, journamalism) has done and is doing to the republic?

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Not funny at all

Beyond that I'll just say this: there better not turn out to be even a shred of evidence that any part of this was exaggerated or timed or hyped for any reason that's not related with absolute certainty to the requirements of the police and counterterrorist community. Bush and Blair better be purer than Caesar's wife on this one.

Read the whole thing

For the uninitiated, the "Caesar's wife" bit explained

In a nutshell

The Daily Show, via Crooks and Liars

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Just 'cause

sometimes it's useful to pause for a bit of perspective (although we might be mindful of Douglas Adams's thoughts on this. . . .), and because I'm still learning to do more than merely post text (and practice is good): from Astronomy Picture of the Day, which is itself worth a bookmark.

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Yet more ipedia

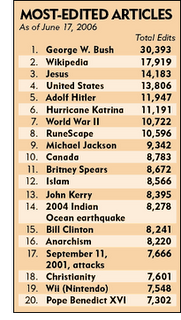

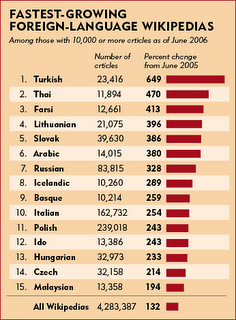

Yet another essay on Wikipedia, courtesy of The Atlantic.

Two tables from the article, a nice companion piece to the JAH and New Yorker pieces (scroll down to The World's Most Ambitious Vanity Press):

Dr. Stewart, therapist

The anchor-as-shrink analogy recalls Philip Rieff's 1965 book The Triumph of the Therapeutic, in which he defined the "psychological man," who shuns the messy realities of the public arena and turns inward to address his own interests and emotions. We might postulate that the psychological Stewart fan disengages from politics not out of selfishness or ignorance but out of a sense of helplessness—the kind of hysterical-in-all-senses incredulity that produces some of The Daily Show's giddiest contact highs.

Naming is a political act

What is the name of a certain political party in the United States—not the one which controls the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the federal government but the other one, which doesn’t? The question is a small one, to be sure: a minor irritation, a wee gnat compared to such red-clawed, sharp-toothed horrors as the health-care mess and the budget deficit, to say nothing of Iraq and Lebanon. But it has been around longer than any of them, and, annoyingly, it won’t go away.

Last week, the gnat was buzzing at a high altitude. . . .

The Stuarts invented the internet

To live up to its billing, Internet journalism has to meet high standards both conceptually and practically: the medium has to be revolutionary, and the journalism has to be good. The quality of Internet journalism is bound to improve over time, especially if more of the virtues of traditional journalism migrate to the Internet. But, although the medium has great capabilities, especially the way it opens out and speeds up the discourse, it is not quite as different from what has gone before as its advocates are saying.

Societies create structures of authority for producing and distributing knowledge, information, and opinion. These structures are always waxing and waning, depending not only on the invention of new means of communication but also on political, cultural, and economic developments. An interesting new book about this came out last year in Britain under the daunting title “Representation and Misrepresentation in Later Stuart Britain: Partisanship and Political Culture.” It is set in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and although its author, Mark Knights, who teaches at the University of East Anglia, does not make explicit comparisons to the present, it seems obvious that such comparisons are on his mind.

The “new media” of later Stuart Britain were pamphlets and periodicals, made possible not only by the advent of the printing press but by the relaxation of government censorship and licensing regimes, by political unrest, and by urbanization (which created audiences for public debate). Today, the best known of the periodicals is Addison and Steele’s Spectator, but it was one of dozens that proliferated almost explosively in the early seventeen-hundreds, including The Tatler, The Post Boy, The Medley, and The British Apollo. The most famous of the pamphleteers was Daniel Defoe, but there were hundreds of others, including Thomas Sprat, the author of “A True Account and Declaration of the Horrid Conspiracy Against the Late King” (1685), and Charles Leslie, the author of “The Wolf Stript of His Shepherd’s Cloathing” (1704). These voices entered a public conversation that had been narrowly restricted, mainly to holders of official positions in church and state. They were the bloggers and citizen journalists of their day, and their influence was far greater (though their audiences were far smaller) than what anybody on the Internet has yet achieved.

As media, Knights points out, both pamphlets and periodicals were radically transformative in their capabilities. Pamphlets were a mass medium with a short lead time—cheap, transportable, and easily accessible to people of all classes and political inclinations. They were, as Knights puts it, “capable of assuming different forms (letters, dialogues, essays, refutations, vindications, and so on)” and, he adds, were “ideally suited to making a public statement at a particular moment.” Periodicals were, by the standards of the day, “a sort of interactive entertainment,” because of the invention of letters to the editor and because publications were constantly responding to their readers and to one another.

Then as now, the new media in their fresh youth produced a distinctive, hot-tempered rhetorical style.